Cable Cars, Streetcars, and Inclines

Rail transit in Cincinnati was the result of a number of incremental changes over prevailing transit modes. Horse-drawn carriages evolved over time into omnibuses designed to carry more people. In the mid-1800’s, metal rails were embedded in streets to reduce friction and allow the horses to pull greater loads. By 1880, eight horsecar lines extended beyond the central basin 1.

Cincinnati’s steep hills presented a number of challenges to extending transit lines outside the basin. This obstacle was solved, in part, by the development of several inclines which gave rise to Cincinnati’s earliest suburbs. The inclines functioned as a cross between railroad and elevator, with horsecars, cable cars, and streetcars being driven onto level platforms, which were then pulled by cables along a sloped track to the top of the hill. In most cases, a typical incline consisted of two tracks, with counterbalanced platforms operating on each track. Beginning in 1872, a total of five inclines were built, with the last one ceasing operation in 1948 2. The masonry foundations of some inclines are still visible on Cincinnati’s hillsides today.

Cincinnati had a brief flirtation with cable cars similar to those still operating in San Francisco, with three routes operating by the mid-1880’s. However, by within twenty years all three had been either converted to electric streetcars or abandoned 3.

In 1889, Cincinnati saw the introduction of the first electric streetcar on the Main Street line 4. Within a few years, most of the remaining horsecar and cable car lines had been electrified. Cincinnati’s streetcar system was somewhat unique in that electric power was provided by two overhead wires, one serving as the supply and the other serving as the return. In most systems, streetcars operated under a single supply wire, with the running rails acting as the ground return.

Despite a violent strike by the Cincinnati Traction Company in 1913, electric streetcars continued to flourish. From the late 1800’s through the 1940’s, the streetcar became the dominant mode of public transit in the Cincinnati area. At its peak, the system encompassed over 200 miles of track, and annually served over 100 million passengers for decades 5.

The Subway

In 1916, Cincinnati voters approved a $6M bond issue to construct a 16-mile rapid transit loop, partially utilizing the bed of the former Miami & Erie Canal for a downtown subway tunnel under what would become Central Parkway. The system was envisioned to serve city subway trains as well as interurban trains, with interurbans terminating at Race Street. The rapid transit stations were designed to the same specifications as what is now the MBTA Red Line that serves Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts 6.

Construction began in 1920, but World War I and the associated cost escalation of construction materials since the 1916 bond issue effectively doomed the project. By 1925, the $6M in funding had been exhausted, and construction ceased. Approximately two miles of subway tunnel, three shorter tunnels, and seven miles of above-ground grading complete. The nine completed miles of the system included four subway stations and three above-ground stations, but did not include track, power distribution, station finishes, or rolling stock 7.

Although a number of large infrastructure projects were undertaken in Cincinnati as part of the Works Progress Administation (WPA) program during the Great Depression, the subway was not one of them. One station was stocked as a civil defense shelter during the Cold War, and a large water main was built along one trackway in the 1950’s. The above-ground portions of the system were used as the local match for federal highway funding during the post-war years, with the rights-of-way now occupied by Interstate 75, the Norwood Lateral Expressway, and Interstate 71.

The subway tunnels and stations remain under Central Parkway, with visible portals and vent grates on the surface belying their existence. Although the subway never saw passenger service, the infrastructure is still inspected and maintained by the city, and periodic tours are offered to the public. In recent years, discussion of a regional light rail system has renewed interest in completing the subway for transit use.

The Decline of Passenger Rail Transit

As typical with most American cities, the postwar years saw a rapid rise in private automobile use combined with a corresponding decline in passenger rail transit. The unfinished subway right-of-way was commandeered for freeway construction in the 1950’s, and the 1970’s saw the demolition of the magnificent passenger concourse at Union Terminal. Signifying the rising importance of air travel, several of Union Terminal’s famed murals were relocated to the new international airport across the river in Boone County, Kentucky.

On April 29, 1951, William Klappert piloted an orange streetcar into the car barn and removed his change-maker and lunch box, ending the streetcar era in Cincinnati. Since then, buses have provided the only form of public transit in the Greater Cincinnati area. Streetcars had already ceased running in Northern Kentucky several years earlier 8. As of this writing, Cincinnati’s only intercity passenger rail service is Amtrak’s Cardinal, which calls at Union Terminal three times a week in each direction between New York and Chicago.

Metro Moves

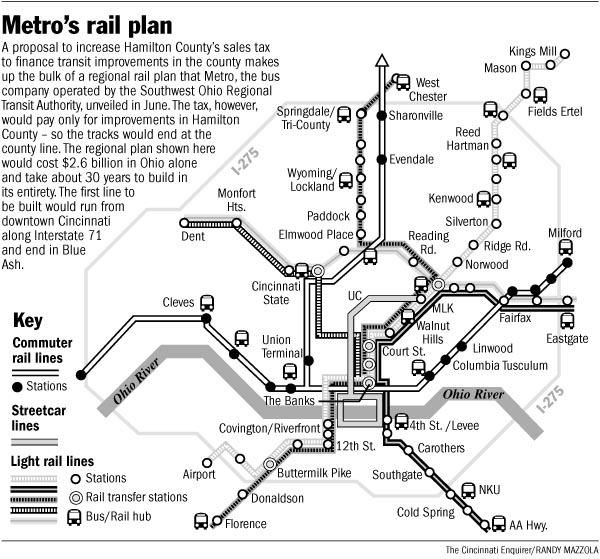

In 2002, the Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Authority (SORTA) placed Issue 7 on the general election ballot for Hamilton County. The so-called “Metro Moves” plan envisioned a radical change of priorities for public transit in Cincinnati, focusing on the construction of an extensive network of light rail, commuter rail, and streetcar lines serving the region. Issue 7 would have involved a half-cent sales tax levy for public transit improvements in the region, including five light rail lines, three commuter rail lines, a streetcar circulator, and an expansion of the bus system. The plan would have provided light rail service from downtown to the airport and several suburban destinations, and made use of the abandoned subway for light rail use.

In November, voters rejected the measure by a 2-1 margin 9. A number of factors led to the demise of Metro Moves. Voters had recently passed a half-cent sales tax levy to build two new sports stadiums on the riverfront, whose construction costs came in significantly over-budget. Additionally, Cincinnati mayor Charlie Luken and Congressman Steve Chabot actively opposed the project. Opponents of Metro Moves painted it as a “boondoggle”, with opposition led by Stephan Louis and a coalition known as ALERT, or Alternatives to Light Rail Transit. In 2003, the Ohio Elections Commission found Louis guilty of making false statements in television ads in opposition to the Metro Moves plan. Despite this, Louis was appointed to serve on SORTA’s board of directors and remained on the board until 2009 10.

The Streetcar and Issue 9

Recent years have begun to see a renewed interest in passenger rail transit in the Cincinnati area. Mayor Mark Mallory, elected to office in 2005 and reelected in 2009, has made construction of a downtown streetcar circulator a main priority for his administration. Steve Driehaus defeated Rep. Steve Chabot in 2008, and has spoken in favor of the streetcar project and passenger rail transit in general.

The City envisions a surface-running streetcar route from downtown to Over-the-Rhine and the Uptown university / medical district, utilizing modern low-floor streetcars similar to those in use in Portland, Seattle, and Tacoma.

In 2009, opponents of the streetcar formed an alliance consisting of the local chapter of the NAACP, the Ohio Green Party, and an anti-tax group known as COAST (Coalition Opposed to Additional Spending and Taxes) to force a ballot measure that would have amended the city Charter so that no money could be spent on the construction or improvement of passenger rail facilities without first submitting the matter to a referendum. The local NAACP chapter, led by a political opponent of Mayor Mallory, claimed the streetcar would lead to increased gentrification in the largely African-American Over-the-Rhine neighborhood. The Green Party opposed the project because the electricity used to power the streetcars is generated by coal-fired power plants, and COAST opposes the project out of fears of increased taxes, although no tax increases are planned for funding of the streetcar project.

In 2009, opponents of the streetcar formed an alliance consisting of the local chapter of the NAACP, the Ohio Green Party, and an anti-tax group known as COAST (Coalition Opposed to Additional Spending and Taxes) to force a ballot measure that would have amended the city Charter so that no money could be spent on the construction or improvement of passenger rail facilities without first submitting the matter to a referendum. The local NAACP chapter, led by a political opponent of Mayor Mallory, claimed the streetcar would lead to increased gentrification in the largely African-American Over-the-Rhine neighborhood. The Green Party opposed the project because the electricity used to power the streetcars is generated by coal-fired power plants, and COAST opposes the project out of fears of increased taxes, although no tax increases are planned for funding of the streetcar project.

The proposed amendment change became known as Issue 9, and read as follows:

Shall the Charter of the City of Cincinnati be amended to prohibit the city, and its various boards and commissions, from spending any monies for right-of-way acquisition or construction of improvements for passenger rail transportation (e.g. a trolley or streetcar) within the city limits without first submitting the question of approval of such expenditure to a vote of the electorate of the city and receiving a major affirmative vote for the same, by enacting new Article XIV?

As most federal transit funding requires quick action by localities to receive it, the passage of Issue 9 would have effectively outlawed any form of passenger rail transit in the city of Cincinnati. Transit advocates in Cincinnati quickly mobilized a “No on 9” campaign, and were ultimately successful on Election Day.

As of this writing, preliminary engineering continues for the streetcar project as the city awaits federal funding for construction. If funding is received in 2010, the streetcar could begin passenger service as early as 2012. A regional light rail system remains an active topic of discussion among grassroots transit advocates, but to date no formal planning is underway by government officials.

Further Reading

Notes

- Northern Kentucky University (NKU) Department of History and Geography, “Historical Atlas of Cincinnati:Â The Relationship Between Transportation and Urban Growth in Cincinnati”, http://www.nku.edu/~hisgeo/AtlasProject/index.htm [accessed 18 February 2010].

- NKU

- NKU

- Dick Perry, Vas You Ever in Zinzinnati: A Personal Portrait of Cincinnati, New York: Weathervane Books, 1966, p. 67.

- Tom O’Neil, The Cincinnati Enquirer, “Exhibit Commemorates the Streetcar Era”, 18 August 2001.

- Jake Mecklenborg, “Cincinnati’s Abandoned Subway”, Cincinnati-Transit.net, http://www.cincinnati-transit.net/subway-section3.html [accessed 18 February 2010].

- Mecklenborg

- Perry, p. 120.

- James Pilcher, “Metro Plan Hits Wall of Resistance”, The Cincinnati Enquirer, 6 November 2002.

- James Pilcher, “Opponent of Light Rail Considered for Seat on Regional Transit Board”, The Cincinnati Enquirer, 8 October 2003.