California Dreamin'

A few weeks ago I had the opportunity to visit Los Angeles for the first time on a business trip. The vast majority of my transit-related expertise so far has been from transit systems that I’ve experienced first-hand, particularly in Chicago and along the East Coast. From that perspective, Los Angeles had never spent much time on my radar screen, and I had at least partially bought into the stereotype of LA as an unwalkable, automobile-dependent suburban wasteland. To be sure, I saw plenty of areas that fit that description, and after spending an afternoon on the 405 freeway, I vowed never to complain about Cincinnati traffic again.

Nevertheless, while I didn’t have the opportunity to do as much exploring as I would’ve liked (most of my time was spent documenting light fixtures and floor finishes inside an Orange County department store), what little I saw of LA’s transit system during my brief visit prompted some additional research once I got back home, and what I found was fascinating and encouraging for the future of public transit in that city and beyond. The story of public transit and urban planning in Los Angeles forms an arc of ambitious beginnings, a tragic fall from grace, and modern-day redemption.

Streetcar City: Golden Age and Decline

Despite the stereotype of Los Angeles as a traffic-choked web of freeways, the central core of Los Angeles owes its form to what was once the largest streetcar network in the world. Although the streetcars themselves are gone, the urban form that remains is a direct legacy of the city’s streetcar system.

Like most other cities, the Los Angeles streetcar system had modest beginnings in the form of horesecars, with LA’s first horsecar line opening in 1874 as the Spring and West 6th Street Railroad. The first electric streetcar in Los Angeles began operation in 1887, two years before electric streetcar service began in Cincinnati. In the late 1800’s Los Angeles also briefly boasted of an extensive cable car system similar to that of San Francisco, but as with cable cars in Cincinnati, most lines were eventually either converted to electric streetcar operation or abandoned by the turn of the 20th Century. Los Angeles has one surviving incline, the Angels Flight, serving the downtown neighborhood of Bunker Hill.

Through a series of mergers and acquisitions, streetcar service in greater Los Angeles during the first half of the 20th Century came to consist of two dominant players: The Los Angeles Railway (the “Yellow Car”) and the Pacific Electric Railway (the “Red Car”). The former was a narrow-gauge streetcar system that primary served downtown Los Angles and a number of neighborhoods close to the central core of the city, while the latter consisted of standard-gauge streetcar and interurban lines that reached as far east as San Bernardino, as far north as the San Fernando Valley, and as far south as Long Beach and Orange County. At their respective peaks, the Los Angeles Railway operated 20 lines on 642 miles of track, while the Pacific Electric Railway operated over 2700 trains daily on over a thousand miles of track, including a short subway and terminal building in downtown Los Angeles.

Los Angeles experienced a period of rapid growth during the early part of the 20th Century, when the city’s streetcar network was at its most extensive. As a result, many parts of the city and surrounding suburbs were urbanized along the streetcar lines, and today, the most densely-populated parts of the city remain neighborhoods and corridors that developed in response to the streetcars.

Over time, though, the streetcars became victims of their own success. Increased traffic congestion in the rapidly-growing city slowed down service, and a number of populist politicians rallied against real and perceived abuses of the public trust by the traction companies. The private automobile was seen as the new and progressive form of transportation, and extensive freeway systems began to appear on drawing boards as early as the 1930’s. (Early proposals for Southern California freeways included dedicated rights-of-way for bus and/or rail transit service, but it has only been in recent years that such ideas have been implemented.)

With the rise in private automobile ownership came a corresponding rise in the financial and political power of the companies that manufacture automobiles and sell gasoline, tires, and other car-related products and services. General Motors, in partnership with Firestone Tire, Standard Oil of California (now Chevron) and Phillips Petroleum formed a holding company called National City Lines. The purpose of the company was to buy or otherwise gain control of various streetcar systems throughout the country, and dismantle the systems in favor of diesel-powered buses. By the late 1940’s, National City Lines and its subsidiaries owned or controlled over a hundred streetcar systems in the United States, including the Yellow Car in Los Angeles. In 1949, General Motors, Standard Oil of California, Firestone and others were convicted of conspiring to monopolize the sale of buses and related products to local transit companies controlled by National City Lines and other companies. The corporations involved were fined $5000, and their executives were fined one dollar each. But the damage had already been done in Los Angeles and elsewhere. On March 13, 1963, a full thirteen years after streetcar service ceased in Cincinnati, the last remaining streetcar lines in Los Angeles were shut down. The next three decades of urban growth in the Los Angeles area would be defined by extensive freeway construction and chronic traffic congestion.

Los Angeles Today

Los Angeles would remain without any form of large-scale rail transit until the opening of the Metro Blue Line light rail line in 1990. Over the following years, newer additions of the region’s rail transit system would include the Green and Gold light rail lines, the Red and Purple heavy rail subway lines, the Metrolink commuter rail system, and several bus rapid transit (BRT) lines. What follows is a brief description of the various modes of transit in the Los Angeles area.

Light Rail

As described elsewhere on this site, the term “light rail” is a broadly-defined form of rail transit that can refer to anything from a slightly larger form of a streetcar (such as Boston’s Green Line) to something that falls just shy of a full-blown heavy rail subway system. Light rail in Los Angeles falls sharply toward the latter end of that spectrum. All light rail trains on the LA Metro have high-level boarding, similar to heavy-rail subway trains, and some Blue Line and Gold Line trains operate with three articulated light rail vehicles (LRVs), reaching the approximate length of a six-car subway train. With few exceptions, most light rail lines operate in dedicated rights-of-way.

The Blue Line, the region’s first light rail line, opened in 1990 and serves a 22-mile-long corridor running due south from downtown Los Angeles to Long Beach. The Blue Line runs in a dedicated subway tunnel in downtown Los Angeles and on surface streets near downtown LA and in Long Beach, but most of the route utilizes the four-track Pacific Electric right-of-way. The Blue Line provides a transfer to the Red Line and Purple Line subway at the Metro Center station downtown, and a transfer to the Green Line at the Imperial / Wilimington / Rosa Parks station.

The Green Line, opened in 1995, runs on an east-west route across the southern portion of Los Angeles, primarily in the median of the 105 freeway. The Green Line is fully grade-separated, with a dedicated right-of-way along its entire route. As of this writing, the Green Line has an indirect connection to Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) via shuttle bus, although future proposals call for a branch of the line to extend directly to the airport itself in conjunction with the proposed Crenshaw Corridor. The Green Line’s only connection to the rest of the Metro rail system is at the aforementioned transfer point to the Blue Line.

The most recent light rail line to begin service in Los Angeles is the Gold Line, which operates a C-shaped route between Pasadena and East Los Angeles, via downtown Los Angeles. The Gold Line right-of-way consists of underground, at-grade, and elevated segments, and connections are available the Union Station for the Red Line and Purple Line subway as well as Metrolink commuter rail service and Amtrak intercity rail service.

Subway

In 1993, the Red Line subway opened for passenger service, becoming the first subway line in Los Angeles and the second heavy-rail subway (after the BART system in San Francisco) on the West Coast. The line is fully underground (except for the railcar storage yards and maintenance facilities), and runs from Union Station downtown to North Hollywood in the San Fernando Valley, via Wilshire Boulevard, Vermont Avenue, Hollywood Boulevard, and a segment that passes under the Santa Monica Mountains.

In 2006, a short branch of the Red Line that continued west under Wilshire Boulevard was re-branded the Purple Line. The Red Line and Purple Line share the same right-of-way from Union Station to Wilshire / Vermont. Traveling west, Red Line trains branch off to the north under Vermont Avenue, while Purple Line trains continue west and serve two additional stations. Current plans call for an extension of the Purple Line west to Santa Monica.

The following amateur video shows an arriving Red Line train, a brief ride on board, and a departing train at Hollywood / Vine:

Commuter Rail

The Los Angeles region is served by the Metrolink commuter rail service, which operates seven commuter rail lines, most of which terminate at historic Union Station in downtown Los Angeles. (The Inland Empire – Orange County Line is the only line that doesn’t directly serve downtown Union Station, but runs between San Bernardino and Oceanside, via Anaheim.) Metrolink operates on tracks shared by Amtrak and freight railroads, using bi-level passenger coaches pulled by diesel locomotives.

Buses and BRT

In addition to local bus service, LA Metro operates a number of express, limited-stop, and bus rapid transit (BRT) services. The Metro Rapid provides limited-stop, high-capacity service along many of the city’s major commercial thoroughfares, while Metro Liner service offers true BRT service in two corridors: The Orange Line that feeds into the North Hollywood station on the Red Line subway, and the Silver Line that operates on a route roughly parallel and to the west of the Blue Line. The Orange Line primarily uses a dedicated transitway, while the Silver Line utilizes high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes on the I-10 and 110 freeways.

In addition to local bus service, LA Metro operates a number of express, limited-stop, and bus rapid transit (BRT) services. The Metro Rapid provides limited-stop, high-capacity service along many of the city’s major commercial thoroughfares, while Metro Liner service offers true BRT service in two corridors: The Orange Line that feeds into the North Hollywood station on the Red Line subway, and the Silver Line that operates on a route roughly parallel and to the west of the Blue Line. The Orange Line primarily uses a dedicated transitway, while the Silver Line utilizes high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes on the I-10 and 110 freeways.

In addition to bus service provided by the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro), a number of other municipal transit agencies also operate bus service in the Los Angeles region.

Future Los Angeles

Although Los Angeles lacked any form of rail transit during the bulk of the post-war years and freeways now criss-cross the region, the central core still owes its urban form largely to the streetcars that once plied down the city’s major boulevards. Combined with chronic traffic congestion and ever-rising gas prices, Los Angeles is primed to utilize the full benefits of rail transit. In the blog Human Transit, Jarrett Walker ponders if Los Angeles might be the next great transit metropolis:

Los Angeles may still seem hopelessly car-dominated today, but it’s fortunate in its urban structure, in ways that make it a smart long term bet as a relatively sustainable city, at least in transport terms.  Two things in particular: (a) the presence of numerous major centres of activity scattered around the region, and (b) the regular grid of arterials, mostly spaced in a way that’s ideal for transit, that covers much of the city, offering the ideal infrastucture for that most efficient of transit structures: a grid network.

Because Los Angeles is a vast constellation of dense places, rather than just a downtown and a hinterland, it’s full of corridors where there is two-way all-day flow of demand, the ideal situation for cost effective, high quality transit. In this, Los Angeles is more like Paris than it is like, say, New York. Much of the core area between downtown and Santa Monica is covered by a braid of major boulevards, all with downtown at one end and the naturally dense coastal strip at the other, every one a potentially great transit market given appropriate protection from traffic. Near the coast, the massive dense nodes of Westwood/UCLA and Century City (and to a lesser extent Santa Monica and Venice) offer further anchoring to the western end of these markets. On a smaller scale, similar anchors are found throughout much of the region. While gathering people to a transit stop will still be difficult, it will be especially easy to grow an everywhere-to-everywhere network in Los Angeles, becuase of these patterns.

The entire article is well worth a read. The author goes on to cite how Angelenos have come to fully embrace the potential of public transit, and a popular mayor has expended considerable political capital on ambitious proposals for public transit projects in Los Angeles.

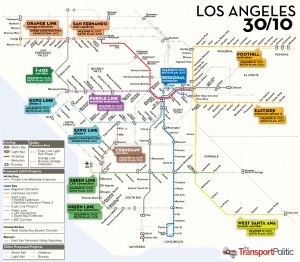

In 2008, Los Angeles County voters approved Measure R with 67.22% of the vote, which raised the county sales tax by one-half a cent to fund transit projects throughout the region. Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa has been advocating for changes to federal law that would allow the LACMTA to borrow capital funding from the federal government, to be paid back over time with future Measure R revenues. If enacted, this would not only allow 30 years worth of transit infrastructure to be completed within ten years, but also have wide-ranging impacts for capital funding in cities far beyond Los Angeles, including Cincinnati.

As a result of the passing of Measure R and other initiatives, a number of ambitious rail transit projects are either under construction or are in active planning phases. A few of the most prominent projects are briefly outlined below:

Under Construction

The first phase of the Expo Line, the region’s newest light rail line, is currently about 90% complete, and is expected to begin revenue service in late 2011. Phase two is expected to be operational by early 2015. This will be the first rail service from downtown Los Angeles to Santa Monica since 1953, and utilizes the former Air Line of the old Pacific Electric Railway. The Expo Line will share the Blue Line’s right-of-way into downtown Los Angeles and connect with the Red Line and Purple Line subway at Metro Center.

The Foothill Extension is a planned 23.9-mile extension of the Gold Line east from Pasadena to Montclair. The route follows the old Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway right-of-way, and includes 12 new stations. The ceremonial groundbreaking for the first phase of the project was held in June 2010.

On the Boards

Mayor Villaraigosa’s top-priority transit project is an extension of the Purple Line subway west from its current terminus at Wilshire / Western to Santa Monica. Dubbed the “Subway to the Sea”, the project would entail 12-14 miles of new subway tunnels and twelve new stations.

The Crenshaw Corridor is a proposed light rail line through southwest Los Angeles from the Purple Line subway to the Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). The 8.5-mile route would include ten new stations and provide connections to the Purple Line, Expo Line, and Green Line.

The Regional Connector is a proposed extension of the Blue Line and Expo Line subway north and east from their current terminus at Metro Center to the Gold Line at Little Tokyo. In addition to providing three new light rail stations in downtown Los Angeles, the project would allow direct transfers between the Gold Line and the Blue / Expo Lines, as well as through-routing of the Blue Line and Expo Line trains onto the Gold Line right-of-way. Instead of terminating downtown, the Blue Line can continue to Pasadena and beyond, and the Expo Line can provide crosstown service between Santa Monica and East Los Angeles.

In addition to various proposals involving subways and light rail lines, a modern streetcar has been proposed that would link several destinations in downtown Los Angeles, not unlike the proposed streetcar for Cincinnati’s downtown and Over-the-Rhine neighborhoods. The project has attracted the support of a wide range of downtown interests, and as of this writing, a range of proposed routes through downtown have been narrowed down to seven possible routes for further consideration.

Lessons for Cincinnati

With continued funding and political support, Los Angeles is poised to shed its image as an automobile-dependent urban wasteland. During my visit last month, I was surprised at how much of downtown Los Angeles’s historic fabric is still intact, and at how walkable many areas were. A number of transit-oriented, mixed-us developments have sprung up around existing transit stations, and if even a fraction of the proposed transit projects come to fruition, the possibilities for transit-oriented development in Los Angeles are infinite. As Jarrett Walker writes:

Densities in many places are lower than ideal, but Los Angeles, more than any city in the world, has a virtually inexhaustable supply of infill opportunities, even if typical middle-class and wealthy suburbs are set aside. If a divine hand prohibited the paving of one more square inch of California, the Los Angeles region would keep growing without a pause.

What does this mean for Cincinnati? For starters, if the federal government enacts Mayor Villaraigosa’s 30/10 recommendations, the effects could be far-reaching for every American city. If a future regional transit plan like the 2002 Metro Moves plan were to be enacted by Cincinnati-area voters, we could see completion of a regional rail system within a decade as opposed to the original 30-year plan.

In addition, and perhaps more importantly, the example of Los Angeles proves that no city is beyond redemption when it comes to building a viable mass transit system. Opponents of progress in Cincinnati like to claim that Cincinnati is somehow different from other cities, that “it will never work here.” The truth is, Cincinnati has urban assets that Los Angeles could only dream of having, such as:

- A dense, vibrant urban core that provides a natural hub for any large-scale regional transit system.

- Existing transit-ready rights-of-way, such as the Oasis Line, Central Parkway subway, and Riverfront Transit Center that are already poised to be utilized in a future regional rail system.

- A relatively compact central basin with historic neighborhoods that are already naturally suited for walkable streets and transit-oritented development.

- A diverse array of walkable neighborhood business districts that serve as natural locations for secondary transit nodes and the associated transit-oriented development those nodes invariably bring.

- Significantly lower construction costs in a relatively stable seismic zone, compared to Southern California.

If rail transit can be made to work in Los Angeles, it can be made to work anywhere, including here. The challenges we face in doing so are not technical or geographic challenges, but political. In Los Angeles it took a generation of unbridled freeway construction and chronic traffic congestion to awaken in the populace the potential of rail-based mass transit. A similar awakening is beginning to take hold in Cincinnati, but we face a determined opposition by forces who have a vested self-interest in maintaining the failed status quo. It will take organization and effort to overcome those forces, but it can happen. Cincinnati’s future as an economically viable city depends upon it.

Further Reading

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (LA Metro)Â (official site)

LA Metro:Â Los Angeles Transit History

LA Metro:Â In the WorksÂ

Metrolink (official site)

City of Los Angeles Department of Transportation (official site)

goLAstreetcar: Los Angeles Streetcar, Inc.

Los Angeles Transportation Headlines

The Transit Coalition: Getting Southern California Moving

Move LA: Building a Comprehensive Transportation System in Los Angeles County

Los Angles Transit History Page

Curbed LA: Los Angeles Neighborhood and Real Estate Blog

NYCsubway.org: Los Angeles area transit photos